Fossils for sale

Welcome back!

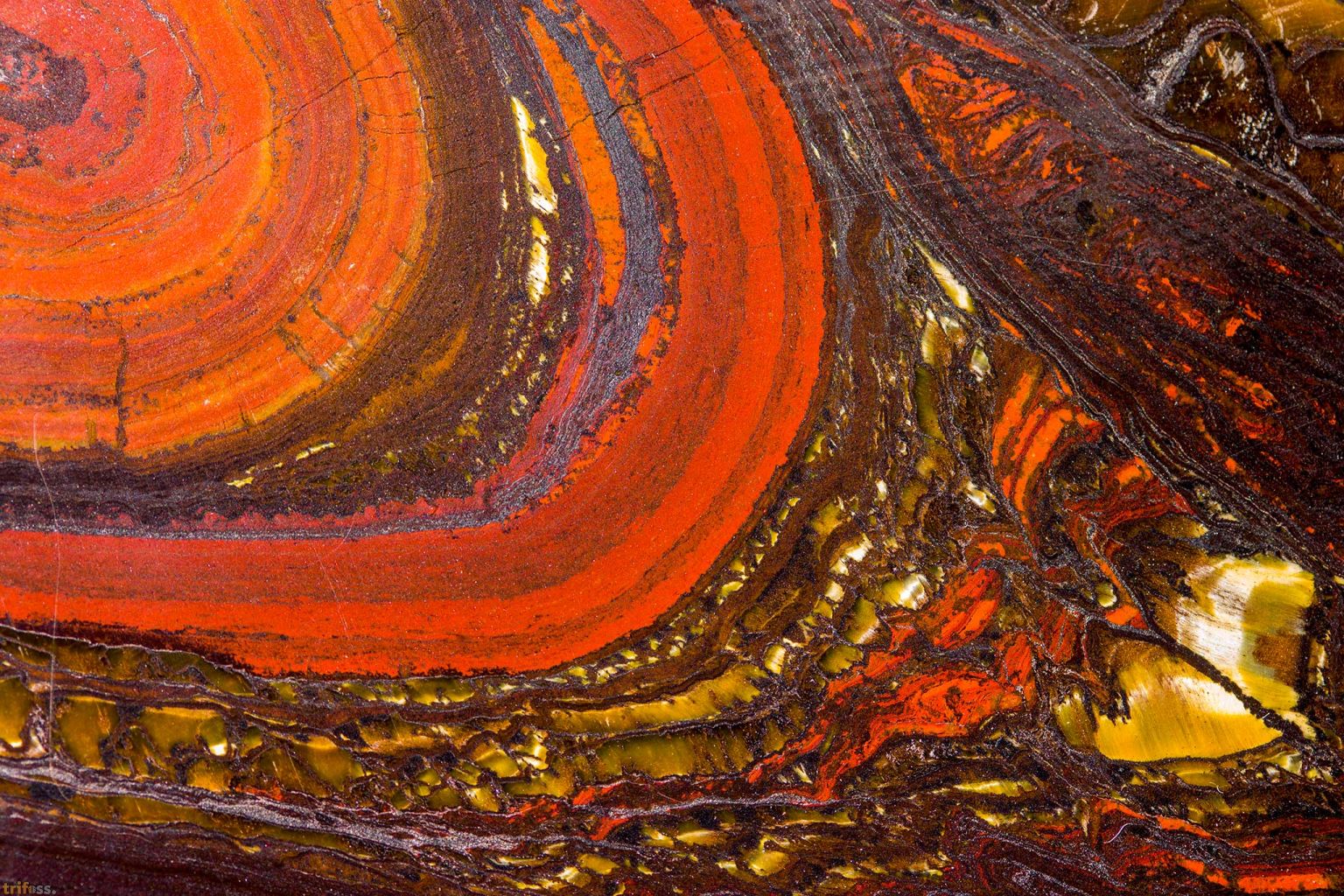

Banded Iron Formation

Banded Iron Formation (BIF), also known as banded ironstone formations, is a distinctive type of sedimentary rock. It consists of alternating layers of iron oxides and iron-poor chert. These formations can be several hundred meters thick and extend laterally for hundreds of kilometers. Most BIFs are of Precambrian age and are believed to record the oxygenation of Earth’s oceans. They formed in seawater due to oxygen production by photosynthetic cyanobacteria. The released oxygen combined with dissolved iron to form insoluble iron oxides, which precipitated out and created thin layers on the ocean floor. Each band in a BIF is similar to a varve, resulting from cyclic variations in oxygen production.

Banded Iron Formation (BIF), also known as banded ironstone formations, is a distinctive type of sedimentary rock. It consists of alternating layers of iron oxides and iron-poor chert. These formations can be several hundred meters thick and extend laterally for hundreds of kilometers. Most BIFs are of Precambrian age and are believed to record the oxygenation of Earth’s oceans. They formed in seawater due to oxygen production by photosynthetic cyanobacteria. The released oxygen combined with dissolved iron to form insoluble iron oxides, which precipitated out and created thin layers on the ocean floor. Each band in a BIF is similar to a varve, resulting from cyclic variations in oxygen production.Banded iron formations were first discovered in northern Michigan in 1844. They account for more than 60% of global iron reserves and are significant sources of iron ore. You can find most BIFs in Australia, Brazil, Canada, India, Russia, South Africa, Ukraine, and the United States. A typical BIF consists of repeated, thin layers of iron oxides (either magnetite or hematite) alternating with bands of iron-poor chert. The iron content in BIFs is typically around 30% by mass, with roughly half the rock being iron oxides and the other half silica.

These formations provide valuable insights into Earth’s history, including the development of cyanobacteria and the enrichment of oxygen in the atmosphere, enabling the evolution of life, including mammals and humans.